Anchoring Bias: Everything You Need to Know!

- Beyond Nudge Team

- Jul 8, 2025

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 31, 2025

Imagine someone researching cars for their daily commute in a traffic-heavy city like Bangalore. They start with a modest budget in mind, say ₹7–8 lakhs for a compact, automatic vehicle. But after weeks of exposure to higher-end models and price tags, that same individual begins to consider options at ₹10 lakhs as a good deal, even though it's above the original budget. Why? Because the perceived anchor has shifted.

This is a real-world glimpse into the Anchoring Bias where the initial piece of information, whether relevant or not, sets the tone for all subsequent judgments.

What is Anchoring Bias?

The anchoring bias (or anchoring effect) is a cognitive bias that causes people to rely too heavily on the first piece of information they receive when making decisions. This "anchor" becomes a mental reference point, shaping how we interpret all subsequent information, even if that information is more accurate or relevant.

This bias affects everyday decisions more than we realise: from how we judge discounts, to how we negotiate salaries, or even how we estimate values in seemingly neutral situations.

The anchoring effect was first introduced by psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman in the late 1970s. Their experiments showed that people’s judgments could be unconsciously swayed by irrelevant, initial information.

The anchor becomes a benchmark: a comparison point for all subsequent judgments.

Mechanisms Behind Anchoring

Anchoring functions on both conscious and subconscious levels. When individuals are exposed to an initial value—regardless of its relevance—they tend to adjust their subsequent judgments in that direction. This adjustment is often insufficient, yet it still pulls their decision closer to the anchor.

For instance, in one study, participants were asked whether Mahatma Gandhi was older or younger than 144 when he died, followed by a guess of his actual age. Despite 144 being clearly unrealistic, their estimates were significantly influenced by that initial number.

In another experiment, participants spun a wheel that randomly landed on a number between 0 and 100. Afterwards, they were asked to estimate how many African countries are members of the United Nations. Those who spun higher numbers consistently gave higher estimates, despite the spin having no actual connection to the question. The arbitrary number acted as a mental anchor, subtly skewing their judgment.

These studies reveal just how effortlessly our brains latch onto the first piece of information we encounter, even when it’s irrelevant, and how difficult it is to correct for that influence, even with conscious effort.

Real-World Examples of Anchoring

The anchoring effect is pervasive in everyday life and can be observed in a multitude of contexts, including negotiations, pricing strategies, and decision-making processes. Consider the following scenarios:

Real Estate Negotiations: When negotiating the price of a house, the initial listing price serves as a potent anchor. Buyers and sellers may unconsciously gravitate toward this initial figure, affecting the final agreed-upon price.

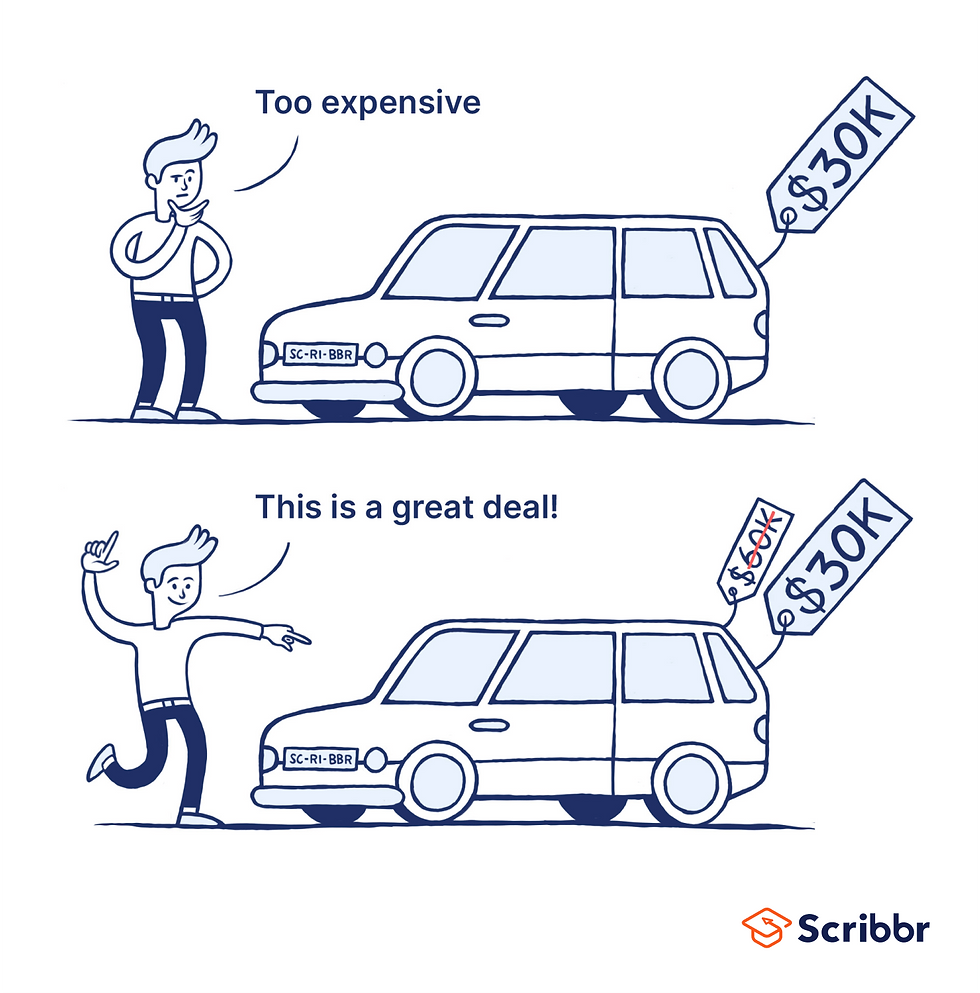

Retail Sales and Discounts: Retailers often use the anchoring effect in pricing strategies. By displaying a higher original price (the anchor) alongside a discounted price, consumers are more likely to perceive the discount as a better deal. We have all fallen prey to the “Slashed prices” tactic. It always makes us feel like we’re getting a better deal than if that previous price anchor wasn’t provided.

Salary Negotiations: In salary negotiations, the first number mentioned; whether by the employer or the candidate; can heavily influence the final salary agreement. The initial figure acts as a reference point that shapes subsequent discussions.

In courtrooms: There was a study conducted in which judges were shown a hypothetical criminal case along with the prosecutor’s expected sentence. Some judges were given a 2months recommendation and others a 34 months. They were first asked to rate if this sentencing was too low, adequate or too high and were then asked to give their own verdict. It was seen that the anchor had a significant effect on the judges’ sentencing. The higher anchor judges on average gave a 29.7 month sentence and the lower gave 18.78 months. External set demands clearly skew judges’ opinions as well despite them being trained to remain completely objective.

Mitigating the Anchoring Effect

The first step is awareness. Knowing that anchoring exists helps you pause and ask:

"Is this number or reference point truly relevant?"

Other ways to counteract anchoring:

Actively seek alternative perspectives before finalising a decision

Compare multiple data points, not just the first one

Slow down: snap decisions are more prone to bias

Neither should a ship rely on one small anchor, nor should life rest on a single hope. - Epictetus

Conclusion

The anchoring effect serves as a reminder that our minds are not always as rational as we might believe. By understanding and acknowledging this cognitive bias, individuals can strive to make more informed and unbiased decisions. Whether in negotiations, financial choices, or everyday judgments, being mindful of the anchoring effect empowers us to navigate the complexities of decision-making with greater clarity and objectivity.

Comments